Amaranth, purslane and dandelion are more than ‘weeds’

Rubí Orozco Santos and V. Quevedo

La Semilla Food Center

This article was originally published in the Las Cruces Sun News» on August 10, 2019.

Amaranth, a staple of indigenous diets and ceremonies across the Americas prior to 1492, was outlawed by the Spanish as part of colonization. La Semilla Food Center

Have you ever considered who defines a weed, or how plants get demoted into that category? It seems any plant that survives human “progress” is called a weed, but a little digging reveals a more alarming origin.

The plants under our feet are a mirror of U.S. history — human settlements, relocations, and forced migrations. Indigenous land stewardship centers on meeting the mutual needs of plants, insects, animals, and human beings for generations to come. Land management by Native Americans was interpreted as untamed wilderness by Europeans, who sought to control the environment to meet only immediate human needs. Unknown or unliked plants — whether they were native to the Americas or introduced by settlers — became weeds.

Dandelions and plantain (European plants considered “weeds” despite their medicinal properties) arrived in the Americas in the 1600s in discarded bedding, fodder and manure. Guinea and Bermuda grasses arrived from Africa through the south. Spanish missionaries and soldiers brought to California the forage plants of the Mediterranean. Clover, a natural nitrogen-fixer, became a weed in the 1950s only because one of the first broadleaf herbicides unintentionally killed it.

Annette Kolodny’s historical study of the frontier from 1630 to 1860 found that frontier men favored “massive exploitation, alteration, and control of the land.” Historian Virginia Scott Jenkins posits that “(this) notion of controlling nature is central to American thinking.” Echoes of this aggressive mindset can be seen in a 1979 magazine advertisement, which told Americans that weeds and cockroaches were “among the hardiest forms of pests with which civilized man must cope” and sold tools operated from an upright position “so you don’t have to stoop to conquer.”

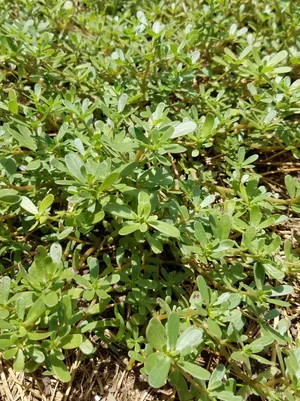

Purslane can be eaten cooked or raw and helps to treat asthma and type 2 diabetes.

La Semilla Food Center

Under pressure to acculturate to this dominant system, the common practice of eating wild greens became socially undesirable despite their high nutritional value. Yet, many of those plants, once “discovered” by Western eyes, become expensive superfoods.

Recent studies show that in neighborhoods more than a mile from a grocery store, the plants we call weeds are more nutritious than what is available at a corner store and even more nutritious than the coveted kale. Research suggests wild plants could fill in the nutrition gap in low-income communities. “Wild foods also contribute to a healthy ecosystem by building soil organic matter, retaining water and nutrients in the soil, and reducing erosion,” according to Philip B. Stark, founder of Berkeley Open Source Food.

The following are just three of the many wild and nutritious plants found in Las Cruces:

- Amaranth/Amaranto: Cultivation of amaranth, a staple of indigenous diets and ceremonies across the Americas prior to 1492, was outlawed by the Spanish as part of colonization; almost eradicated, it’s now called “pigweed.” In India, however, amaranth is known as “Grain of Kings,” and is cultivated for its high nutritional value. Amaranth seeds have more protein than quinoa and more calcium than cow’s milk. It’s leaves contain more iron than spinach. Amaranth helps to reduce cholesterol while providing lysine, iron, fiber, calcium, magnesium, B6 and antioxidants.

- Purslane/Verdolagas: How purslane reached the Americas is unknown, but there is evidence it was eaten by first nations people in the 1400s on the land Ontario now occupies. Purslane can be eaten cooked or raw, and is packed with omega 3 fatty acids, antioxidants, reduces blood pressure, cholesterol, and helps to treat asthma and type 2 diabetes. Purslane also provides ground cover, creating a humid microclimate for nearby plants.

- Dandelion/ Diente de León: This plant has wide-spreading roots that loosen compacted soil and pull nutrients like calcium from deep in the earth to make them available to other plants. Their flowers make them a critical early spring pollinator plant. Dandelions are nutritional powerhouses and edible in their entirety. The greens are rich in beta-carotene, fiber, potassium, iron, calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, B vitamins, and protein. Dandelion stimulates the production of insulin and also aids in liver function. The dandelion’s Latin name is Taraxacum Officinale, meaning “remedy for disorders.”

Dandelions are nutritional powerhouses, stimulating the production of insulin and also aiding in liver function. La Semilla Food Center

Dandelions are nutritional powerhouses, stimulating the production of insulin and also aiding in liver function. La Semilla Food CenterWhile we need our sidewalks and roads to be accessible, they aren’t “dirty” when a little nature pokes through the concrete we have imposed on the land. Plants like dandelion, desert globemallow, mustard and catsear attract pollinators, which are vital to our food supply. Sunflowers, ragweed and mustard extract heavy metals and toxins from our environment.

Rather than seeing unwanted, unattractive plants, can we appreciate their push to survive, and perhaps even their reaching out to help us?

Sources: Berkeley Open Source Food, Tepoztlan: Village in Mexico, Turf War, The Lawn: A history of an American Obsession.

This article is part of a series by La Semilla Food Center that seeks to spark curiosity in and increase appreciation for the Chihuahuan Desert ecosystem.