Life Origins: Painting, Place, and Culture

Artist Al Woody brings El Paso’s stories to the community

Interview by Rubi Orozco Santos and Michelle Carreon

This article was originally published on BorderLore.org» on July 21, 2021.

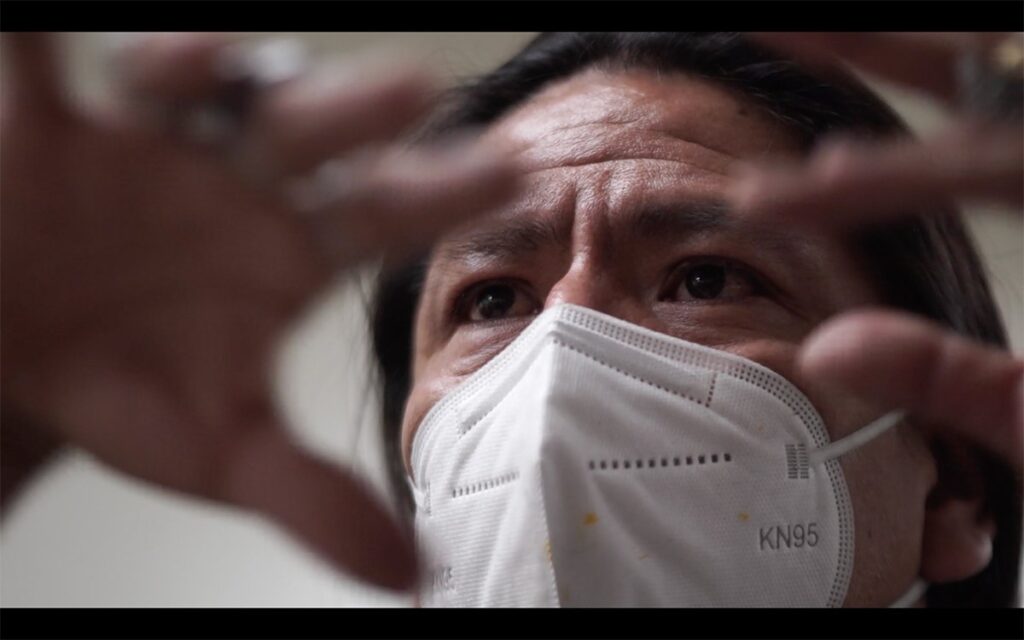

Al Woody is a Diné artist living and working in El Paso, Texas, in part of the river valley we currently know as the Paso del Norte Region, which also includes southern Doña Ana County, New Mexico, and Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, Mexico. Originally from Lukachukai, AZ, Al has lived in various states, including Colorado. Through his company, Healing Ways Artistry, Al offers people aesthetic beauty, stories, and—perhaps unexpectedly—heart-to-heart counsel.

We spoke with Al through our roles with La Semilla Food Center, a food justice nonprofit organization based in Anthony, NM, with a practice of farming, community engagement, and advocacy rooted in relationship and respect. Our organization’s efforts to document and amplify histories and lived experiences in our region in relation to food and farming counter dominant narratives about the border and our desert ecologies. Most importantly, through collective story gathering and sharing, we co-create a shared vision for a way forward.

The current pandemic has revealed and exacerbated the various ways that systems of inequity and climate change affect our communities in this region. But also, it has created an opportunity for transformation and reinforced our commitment to strengthening our relationships with each other and to the land. Our stories matter, and storytelling has power to transform and challenge systems that exploit nature and devalue local knowledge and wisdom.

Al collaborated with us as part of this work. Inspired in part by local stories shared by people from across the region in the fall of 2020, as well as his own experience as an Indigenous person and artist, he envisioned the stunning mural “Life Origins” at Bowie High School in El Paso, a historically significant school located just yards from the international boundary. Here, we include highlights from our conversation with Al, in which he reflects and shares stories of his journey as an artist, his life on the border, and the inspiration for his mural.

Becoming an Artist

I was scribbling on my grandmother’s walls when I was a kid. My grandmother would say, “Why are you scribbling on my white walls?” That was my first path towards what I’m doing right now. I always drew everything I saw. The teachers would take away my drawings. I thought they threw them away. One time, I visited one of my teachers, and lo and behold there was my artwork on their walls.

Later I learned the importance of education. I wasn’t really an intellectual, I guess, when I was young. I went to a boarding school on a reservation. It was a different world—from a Native American world to what us Natives call the “white world.” When I went there, it wasn’t nice for me. I had a learning disability. I had a hard time. I didn’t start learning anything until I was in fourth grade. Then I kind of snapped, like, “Wait a minute, this is the real world.” Through much of my life, it seemed like I was just winging it, just showing up to school, doing the best I could. But my artistic ability was my way out.

In school I started to learn more about art. It was a choice between woodshop or art class, so I took art class. But I had other things that kind of obscured my life, and I dropped out of high school. I didn’t go back to school until I was in my early 20s. Graduating was a big thing for me. I worked as a metal roofer for many years and started a family. My wife went to school and got her college degree. I became a supervisor, and I taught metal roofing. Metal roofing was a form of art for me. It was architecture in a way. I learned the trade from good people that taught me. I used to be on the roof way up there pounding nails and screws, lifting metal day by day, and I would be scribbling on boards. Guys would come up to me and tell me, “Al, what are you doing up here on the roof with us roofers when you can do that?” And I never listened. I just kept working. Finally, one day I hurt my back on the job, and that really put a crimp on making my money. I didn’t really know what I was going to do. I was praying about it. I said, “Creator, what am I going to do?” “Well, turn around. There’s pencil and paper right there. That’s what you do,” he told me. So, I started painting and drawing and remembering my childhood, my life, what I’m all about. In rediscovering myself, I found my heritage.

In my past life, I was a burning tire, rolling downhill, bouncing, rolling, burning, bouncing, smoke coming down, into blackness, into darkness. Creator healed me that day, and ever since, I started changing my ways and following the Red Road, as we call it in a Native American way. I started transforming my heart, healing, and when my company came about, I had to think of a name. Just out of the blue I said, “Why not Healing Ways Artistry?”

Today, art is all I do, 24/7. From my story, I can tell you what’s in my heart and my life in color, on canvas, and show you what I see.

The Role of the Painter

Art has always been part of human life. Life was formed the first day into a bowl from clay from the earth. That’s art. I told the students at Bowie High School, “Everything that we touch was drawn on paper.” That made them think. Everything has something to do with art. It’s medicine.

I’ve been called to be a painter. If you’re a singer, you sing for the people. Painting is like poetry in the form of color. You’re telling a story. I work for the people. It’s food for them; it’s food for thought. Sometimes you come home from a hard day’s work, and your house is chaos. I tell people, “When you open the door and you see my painting, what will you think? It will change your world. It will bring happiness and harmony to your home.” That’s how I pray for it, you know, I pray for my art that way.

I tell them, “This is a one of a kind, there is no other like it. Like you! You’re one of a kind!” It’s spiritual work, and especially with my life, my past. I tell them my company is called Healing Ways Artistry. People ask, “How come it says ‘healing’?” My life was chaos. I was an alcoholic. I went through hell to find myself. I’m still working every day. I had to overcome all kinds of obstacles in my life to become this artist that I am today. If I hadn’t changed myself, I wouldn’t be sitting here painting. I tell the people the truth of my life. That’s part of my painting. I counsel the people.

Unfortunately, I have made a lot of people cry. They walk away crying holding their paintings because of what I said. It gets deep, describing one’s ability to change another person’s heart with these tools. It gets deep when a farmer puts that seed in the ground and then a few days it starts sprouting and next thing you know in a couple of weeks it’s a plant and next thing you know we’re eating it. And then the seed cycle returns.

The other day someone said, “It’s really windy man, I hate this.” I said, “No, you should love this wind. This wind came from around the world. This dirt, all this dust, comes from Africa, all these nutrients have to come around the world and drop all over these plants like pollen, like the earth is pollinating itself. If these winds don’t come around this time of year, nothing grows. This is a part of life. Winds of change. These winds aren’t for no reason. These sediments that fall from the sky are what lead the plants to grow here.

That’s what I’ve learned from my painting. What type of tree is it? What type of bird is this? All birds aren’t the same. We have to learn the names of things. I have to learn about people, their facial expressions—crying, laughing. Like I said, I wasn’t an intellectual and then I started reading and learning. Creator started pouring stuff into my brain. I said, “Hang on!” And now here I am doing the best I can for the people.

Life on the Border

For me, life on the border feels like I’m at home, with the Navajo. We’re the same people—the same hardships, the same struggle. Except there’s concrete and roads here and electricity and there’s a lot more help. The culture is a little different, but the color is still the same, you know? I’m brown, and the Mexican people are brown. When I came here, I said, “My God, that person looks like the person back home.”

Everybody has to have a job, has to cook, has to do something, work, just like home. It’s no different. People say, “Oh I wanna move to another city,” and it’s the same struggles. Survival. Sometimes they say “survival of the fittest,” but that’s not true. In the Native American world, the fittest ones have to help the ones that aren’t the fittest. We gotta help our people. We gotta nurture their thoughts, their minds, so they can transform also.

This is home for me. I love this place. It has hope for me. It’s really spiritual; it’s powerful here. The other day at Village Inn, I looked out the window and told my daughter, “Let’s see how this place would look without buildings.” So I painted the mountains and said, “This is how it looked before any human came here. And now look there’s people, buildings.” It’s a culture, we have to be here. This is home. The Tiguas live here. The Mexican people are here.

The Mural

Storytelling is deep. When I started painting this mural, I had to hold back tears. I still do. It brings back a lot of hard memories. For me, it goes to the roots, the plants, the animals, the people, their minds, their souls, their hearts, food, water. These are important things that we should be teaching our kids. When I go to Bowie High school, it takes me back to when I was in school. It’s an honor for me to be painting for the kids. I’m a very emotional person. I’m an empath. Art is spiritual for me—what Creator is doing for the people and everybody involved.

I guess I started this mural a long time ago in my mind. Then La Semilla came and the mural came to fruition. Working with La Semilla has made me think so much. Working with the farms and the people, working for the people, feeding the people. That’s really powerful work. I wasn’t just going to throw a mural up. For me, it’s powerful medicine.

My painting connected what I was feeling about farming and nature. Everybody from this area is represented. I try to honor everybody around here that put their hands in the soil to bring life, to bring the food. That’s what the painting is about: to bring restoration to the land; restoration to the young minds that need to think about how we’re going to gain food, especially growing our food. I tell people, especially my kids, when I eat with them, “Somebody grew that, eat it!” That’s what this painting’s about—the culture, food, nature, farming.

In this mural, I painted my grandmother. When I was a kid, my grandmother took me to the cornfields and to gather corn. She would tell me, “Break off the big ones, not the little ones! The big corn!” I was a little guy, breaking them off, and I would stack them in a basket. When we got done, we would walk home together. I would see her skirt flowing in front of me and her moccasins, walking straight forward. We had to walk at least two miles to the fields from home to gather food. And that was for dinner. Like I said, we weren’t rich, so we had to go grow our food.

This is El Paso. I had to put the Franklin Mountains—the core stability of this whole place. I was told stories a long time ago that people came from all over and traded in these routes. That’s why they call this place El Paso—the Pass. I had to put the people in too. Our ancestors, the Mexican ancestors, and how we’re all similar. We all grow corn—from Africa to South America to North America, all over the world. Food, the plants, trees. Farming, the people, the work, the teachings. Teaching young people. If somebody’s not shown how to use a tool, then they’ll never learn. So I painted kids working, picking vegetables and fruit, helping the grown-ups and learning.

I painted a woman grinding corn so she can make flour that turns into tortillas and bread. From a seed to a leaf to a tree to a fruit and then to consumption. All a system. The clouds, the rains. If not for the rains that nurture the ground and water our plants, nothing lives. That’s why I have the Native pots to represent Water is Life. The pots were made from the ground, from the Mother Earth, with water, together, into tools to hold water. Those were our first tools. They made it with their own hands, our ancestors, our grandmothers, our grandfathers, that had traditions, learnings, teachings, culture. Our ancestors worked hard to get us where we’re at right now. On both sides, there’s dancing. Native Americans over here, they’re dancing for harvest, for celebration. They pray the winds come and the rains come, so it will nourish the ground, so the food would grow. That’s what’s represented here by the Tiguas, the local tribe. I didn’t want to just put anyone else into this mural that didn’t come from here. I have the two hands coming from above holding half seeds and half ground. That’s the gift from the Creator.

If we don’t live by these systems, we don’t live. We’re also having climate change in the world. Things are changing. Pollution. All kinds of things happening. That’s what this Native American thinks about and prays about. Everybody around the world has struggles to gain food. I know how it is to be starving and to be without food. We gotta help each other.

Rubi Orozco Santos is a poet, cultural worker, and La Semilla Food Center’s Organizational Storyteller.

Michelle Carreon is an interdisciplinary researcher and the new Food Justice Storyteller at La Semilla Food Center.